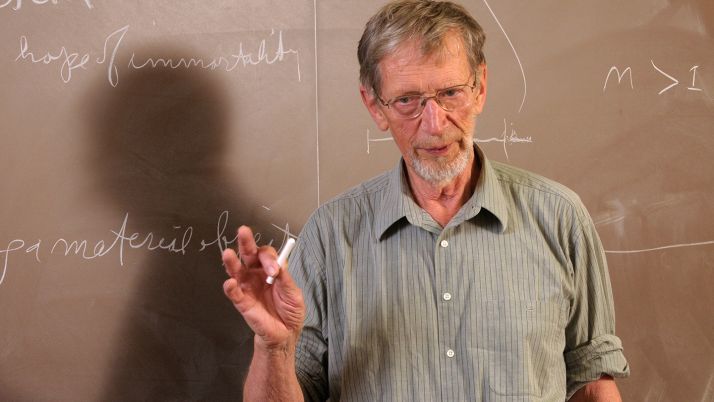

Dean Bok ’60 had every intention of being a lifetime high school science teacher. But in his second year at Valley Christian High School, his principal asked him to teach mathematics, too.

“I told him no,” Bok remembered. “I couldn’t desecrate the field of mathematics.”

It cost Bok his job, and millions of Americans can be glad it did.

Bok saw graduate school as his best alternative. By 1968 he had earned a PhD in cell biology at UCLA and moved directly into his own laboratory there to continue work he’d begun with his mentoring professor on the eye—specifically, on a group of inherited diseases of the retina that will cause blindness in 10 million Americans.

In May 2009, Bok was honored with the Llura Liggett Gund Career Achievement Award from the Foundation Fighting Blindness for his significant contributions to the preventions, treatments and cures of those diseases. The award has been presented only four times in the foundation’s 40-year history. And it’s only the latest in a series of awards for Bok, which includes the highest honor given for vision research by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology and honors from the National Institutes of Health.

By the late 1960s, Bok and his mentor had discovered how healthy photoreceptors—commonly called rods and cones—maintain their youth throughout the human lifespan. In his own lab, Bok discovered how vitamin A, essential for vision, is taken up from the bloodstream into the cells of the retina.

“I think of it as a bucket brigade,” he explained. “There’s a whole brigade of proteins that take vitamin A up into the cell and hand it off in its various derivative forms down the line until it finally gets to the photoreceptor, where it captures photons—the smallest units of light—so we can see.”

In the 1990s, Bok and a colleague discovered that when a certain gene, called RPE-65, is missing or defective, the bucket brigade can’t complete its delivery of vitamin A. They published that discovery in 1998, which laid the groundwork for the first successful gene therapy in human vision. Ten years later, in clinical trials, healthy REP-65 was being implanted in the retinas of children born blind. “A boy who could barely negotiate a room is now riding his bike,” Bok reported.

That cure for just one of the forms of inherited retinal disease has been 40 years in the making. It’s not surprising, then, that Bok considers patience the chief virtue of a successful scientist. “I’ve always gone slowly about the acquisition of data,” he said. “When I’m in a hurry, I make mistakes. That’s true of my hobbies, too.”

Bok has also spent many years researching age-related macular degeneration, a loss of vision that affects 30 percent of people over the age of 70. “I think we’re finally cracking the door open on that one,” he said.

Success has brought him many offers of directorships and other administrative positions. Bok has turned them all down. “The two things I relish are teaching and being in my laboratory,” he said.

After more than 40 years in the lab and the classroom, Bok still finds himself marveling at God’s creation. “It thrills me every time I see the intricacy and complexity of the eye’s processes,” he said. “My faith only gets stronger.”