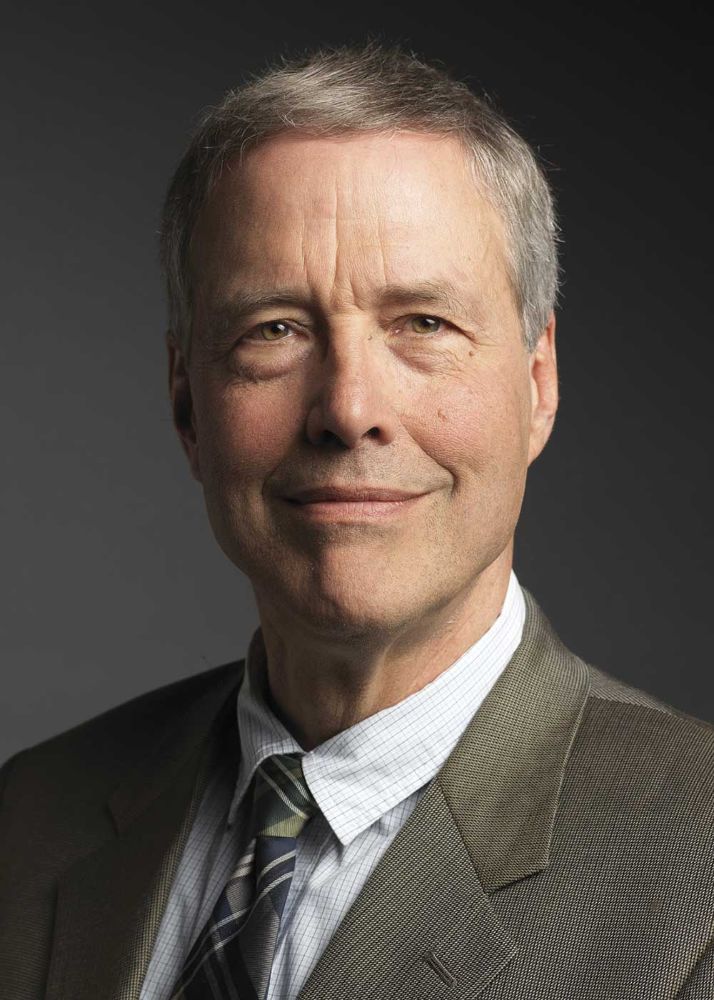

Jim Bratt has his doctoral adviser to thank for a lifelong academic pursuit of Abraham Kuyper, the Dutch theologian, politician and journalist whose influence continues today at Calvin.

Bratt’s PhD dissertation at Yale eventually became his first book, Dutch Calvinism in Modern America, and it contained a chapter on Kuyper, a man Bratt’s adviser found quite fascinating.

“I remember well that he picked up on Kuyper,” Bratt recalled, “and he encouraged me to go further with Kuyper. He thought Kuyper a pretty rare person. And I remember I thought at the time, ‘Yeah, I want to read more Dutch in my life,’ but now, here we are.”

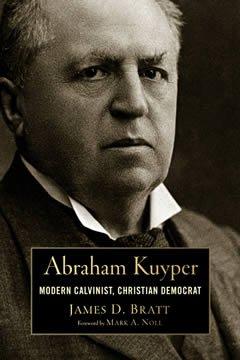

The book already is being called the definitive English-language biography of Kuyper (Bratt noted that several comprehensive Dutch-language biographies of Kuyper exist, including a 600-pager published in 2006). And it is being praised both as a comprehensive history of Kuyper (1837–1920), but also as entirely relevant to 21st-century Christians trying to wrestle with the best ways to engage culture without being swamped by culture.

“I think that understanding the circumstances in which his grand principles emerged can help us relativize his claims where needed but also apply them in relevant, contemporary ways,” Bratt said. “For example, his proposal for apportioning public space amid competing convictions might speak to sites of religious conflict everywhere from Indonesia to Nigeria and from the Balkans to the Middle East. Kuyper’s insights are relevant a hundred years after he voiced them.”

Bratt’s journey with Kuyper began in earnest with a Fulbright Award in 1985 that allowed him to spend six months researching in Amsterdam at the Free University. In 2010 he had another Fulbright and spent four months at the Roosevelt Study Center in Middelburg in the Netherlands. In between, Bratt also read hundreds of Kuyper’s books, sermons, devotionals and more in the United States.

But it was during his two stays in the Netherlands that Bratt was able to research and read a plethora of original Kuyper materials, everything from his hand-written sermon notes to newspaper editorials to letters between Kuyper and his wife.

Those moments studying the man’s thoughts via his own penmanship, in ink fading from black to brown and on paper becoming ever more brittle with age, were some of Bratt’s most personal and most powerful interactions with Kuyper.

He recalls sorting through some of Kuyper’s materials in the Netherlands archives and coming across an envelope marked in Kuyper’s hand with a single Dutch word, “personalia.”

Intrigued, he carefully began going through the contents, finding little of interest and silently observing to himself as he cataloged the contents, “that’s boring, that’s boring, that’s boring.” Suddenly out from one of the envelopes fell a clump of hair.

“I looked on the envelope,” said Bratt, “and it’s written there: ‘From my dear sister.’”

The next envelope, Bratt recalled, contained what looked like a piece of arbor vitae. It was marked “From my mother’s grave.”

“In both cases,” Bratt said, “it took my breath away. There you are touching a person. It’s an intimate moment. For a historian, it’s the motherlode.”

Indeed such moments were an important part of what Bratt sought to help his readers understand about Kuyper through the new book.

“He was a very public man, a very official man,” Bratt said, “but he had a life outside the public eye. He was married, he had kids, he had health problems, a son died. I wanted to write about that man, too.”

Bratt is especially hopeful that the book will be beneficial to Calvin and give students, staff and faculty a “fuller and more systematic awareness of one of the most significant figures in the college’s heritage.”

He added: “To the extent that we live out of—or at least invoke—the ‘Kuyperian tradition,’ we ought to know as much as we can about it so that, whether we would deepen, reject or revise him, we can always more knowledgeably approach Kuyper’s thought and example and gain better understanding of our educational purpose.”