Perhaps the best way to understand Kent County’s Plaster Creek is to start at the end.

The creek begins bucolically in Dutton, Mich., near a park and farmers’ fields. But its finish, some 26 circuitous miles later, comes in a heavily industrial section of Grand Rapids.

There one finds Michigan Paving and Materials to the creek’s east and the city of Grand Rapids impound lot, littered with unclaimed cars and motorcycles, to its west.

And the final few hundred feet of the creek, just before it joins the Grand River, the state’s longest, for an eventual discharge into Lake Michigan, is beneath Market Avenue SW, a four-lane, 45 miles-per-hour thoroughfare where passing motorists give the confluence of the creek and the river scarcely a glance if they notice it all.

Indeed, Plaster Creek enters the Grand less than two miles from downtown Grand Rapids, having traversed all manner of industry, commerce and urban settings along the way, picking up a variety of pollutants and bacteria (including E. coli), heavy metals and assorted other detritus that ultimately make it unsafe by state standards for both full and partial body contact and contribute to its dubious distinction as the most polluted creek in west Michigan.

Although at its closest point the main channel of the creek is still approximately two miles from Calvin, the Plaster Creek watershed—the land area that drains, via various tributaries and ponds, into Plaster Creek—encompasses about 58 square miles. It includes part of the Calvin campus and it is home to almost 350 college employees and another 3,200 or so Calvin alumni.

Thus, a decade ago, in 2004, a group of Calvin College faculty and staff formed the Plaster Creek Working Group to gather information, map the watershed and determine ways in which Calvin might make a difference.

A decade of dedication

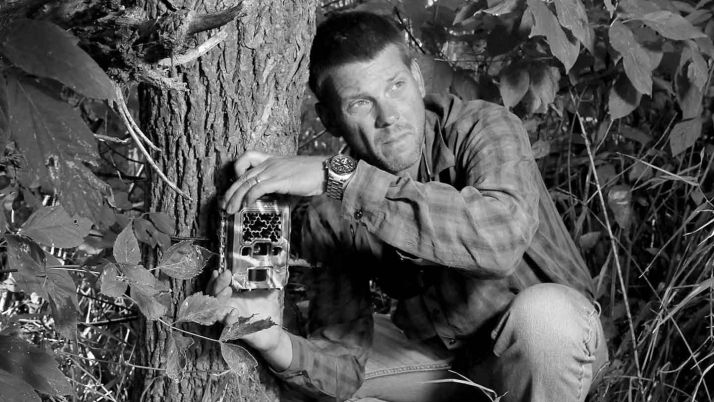

Now, 10 years later the working group has become Plaster Creek Stewards, headed up by Gail Gunst Heffner, Calvin’s director of community engagement; Dave Warners, biology professor; and Mike Ryskamp, program coordinator.

And the college is making a slow-but-sure difference, hosting numerous education events annually, using the creek as a center for curriculum-based research, leading watershed restoration efforts and attracting national attention, the latest being a $1.1 million grant from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. The grant is slated to begin in March 2015 and run for two years, during which it will fund significant research opportunities for Calvin students, educational outreach to diverse community audiences, and three large, on-the-ground restoration projects.

That award followed numerous other such grants in the past. All told the Plaster Creek Stewards have been entrusted with more than $1.6 million since 2011.

For Heffner, Warners and Ryskamp, the money, including the recent grant, is affirming and welcome. It allows the Stewards to do far more than they could otherwise. But, they say, the work began well before the grants came along, and it will continue with or without the funds.

That’s because it’s grounded in firm theological foundations that they

At the college’s 2014 Fall Conference for Faculty and Staff, the trio did a presentation on the Plaster Creek project’s history, present and future, its philosophy and the theology of ecology that undergirds the work.

“It’s striking to us,” said Heffner, “that the theological foundations which we come from see caring for creation as fundamental to being faithful to God.”

She noted a quote that Warners unearthed in Calvin’s Institutes, where he wrote that “

She noted, too, Kuyper’s thoughts in his To Be Near Unto God when he wrote: “From of old the church has pointed to nature and to the Bible as the sources of knowledge of God … the Reformed confession truly and beautifully declares that all creation is as a living book, the letters of which are the creatures. In everything that lives in nature, rustles, throbs and stirs itself, we feel the pulse beat of God’s own life.”

“The words are very powerful but

Added Warners: “I think the church today often has a more utilitarian view of creation. We need reminders that it’s way more than just resources to support our lives.”

Education, Research, Restoration

The work of the Plaster Creek Stewards provides those reminders for the trio and for the many others who have worked on the project over the past decade. That work is concentrated in three key areas: education, research and on-the-ground restoration in the watershed.

“Our goal is to educate the community about watershed ecology and to develop a growing group of people who understand the strengths, needs and problems affecting the Plaster Creek Watershed,” said Heffner.

This education takes many forms, including presentations to community groups, annual summer workshops, media outreach, a website and a growing presence on social media, and an event each spring and fall, which includes both a presentation on Plaster Creek and an opportunity for attendees to participate in on-the-ground restoration work.

In October

On the research front, students in a new “Research Methods” biology class (taught by Warners and other biology department colleagues) are using the Plaster Creek watershed as their laboratory, gathering water quality data, including flow rates and E. coli concentrations.

Students have been changed by the experience, and those transformations are reflected in their journal entries.

Wrote one, echoing Calvin and Kuyper: “As a Christian, I have come to better understand God’s creation and how we Christians view this creation. If we are Christians who confess our love towards God, we also have to love and sincerely take care of God’s creation on earth. It’s not because God forces us to, but because we ourselves are part of that creation and because God reveals himself through that creation.”

Another wrote: “I think the reason this course is so effective (and why I enjoyed it so much) is because it is so hands-on. Not only did we read a book about the theories behind research design, we created our own research project from

And Heffner is heading up an oral history project on the watershed, recording the stories of folks who are largely now senior citizens but remember with delight the days when they played alongside, and in, Plaster Creek and the various other tributaries that feed into the creek as part of its watershed.

A long history

The work of the Stewards will form a long arc. It took a long time for the creek to reach its present state; it will take a long time for it to be restored.

Heffner noted that there was a time in the creek’s history not that long ago when it was a thriving ecosystem as well as a cooling-off place for the many kids, and adults, who lived near its banks.

Prior to that, in the 1600s, when explorer Samuel de Champlain reached west Michigan, the watershed was home to the Odaawaa tribe who called the stream Kee-No-Shay or “water of the walleye” for the species of fish that

But in the early 1800s, as the legend goes, a Native American leader, Chief Blackbird, took a canoe ride in the creek with a missionary who was trying to coax the chief and his people into worshiping indoors. The chief’s response had been that there was a sacred place of great beauty and majesty where he and his people worshiped their god. And so he took the missionary up the creek in his canoe to see the spot.

It was, in fact, a majestic waterfall that gained its descent as the result of a large outcropping of gypsum over which the creek’s waters then spilled.

Warners said he can imagine what that sight must have been like in the setting sun, with the final rays of the day catching the water and the gypsum, providing an impressive explosion of color and sound. But this first encounter by the missionary with the valuable mineral, as the story has it, caused him to take a sample of the rock and send it to Detroit for analysis. When the tests came back, the result was a plaster mill was built near that sacred spot. That fateful decision was part of an inexorable changing of the creek that included not just the abandonment of Kee-No-Shay in exchange for its new moniker, Plaster Creek (named for the plaster that gypsum produces when heated), but also the steady degradation of the creek’s waters.

“As the city of Grand Rapids developed and expanded, the quality of Plaster Creek progressively declined,” wrote Heffner in December 2013 for The Rapidian. “Walleye and brook trout were lost by the early 1900s, and several of the creek’s tributaries were relegated to underground pipes, including a four-mile stretch of Burr Oak Creek, today

Despite the current condition of the creek, those who work on its restoration are heartened by its history and hopeful that it might be restored to its old glory and even, perhaps, earn back its old name.

“It took 100 years for Plaster Creek to get this way,” said Heffner. “We’ve been working on cleaning it for 10 years now, and it’s going to take another 20 years to begin to see measurable improvement.”

The Stewards don’t plan to let up anytime soon. The health of Plaster Creek has implications for many in west Michigan, but its impact extends beyond the region and even beyond the state.

After Plaster Creek mingles with the Grand River and together they make their way into Lake Michigan, from there their contribution flows north into Lake Huron and then down into Lake Erie, over Niagara Falls, into Lake Ontario, through the St. Lawrence Seaway and finally into the Atlantic Ocean, some 1,500 miles from the Plaster Creek headwaters.

“This truly goes beyond west Michigan,” said Heffner, who likes to cite the words of poet and farmer Wendell Berry who wrote that people who live at the lower end of a watershed can’t be isolationists. Eventually, probably sooner

For the Plaster Creek Stewards that Golden Rule, and the words of forefathers like Calvin and Kuyper, provide everyday inspiration, a foundation for the hands-on and practical work of watershed restoration.

Said Heffner: “We have a hopeful vision for what the future might look like.”

Phil de Haan is Calvin's senior public relations specialist.