Always drawn to aviation history, Ryan Noppen thought of chronicling the history of Dutch aviation during his work for a defense contractor in Lafayette, Ind., as a subject matter expert in aviation and military studies.

“I was researching foreign air forces for a simulation program being developed for the Navy, and it dawned on me how little was written in the English language about Dutch aviation, let alone the significant role it played in the early development of air transport,” said Noppen, now the program coordinator for the H. Henry Meeter Center for Calvin Studies at the college.

Noppen was encouraged by the retired Calvin professors with whom he had morning coffee in the Hekman Library, particularly English professor George “Tom” Harper ’49 and President William Spoelhof (who regaled Noppen with stories of flying in aircraft piloted by Prins Bernhard of the Netherlands during World War II).

Harper helped Noppen with a book proposal that was eagerly accepted by Bill Eerdmans ’47 at the famous publishing company.

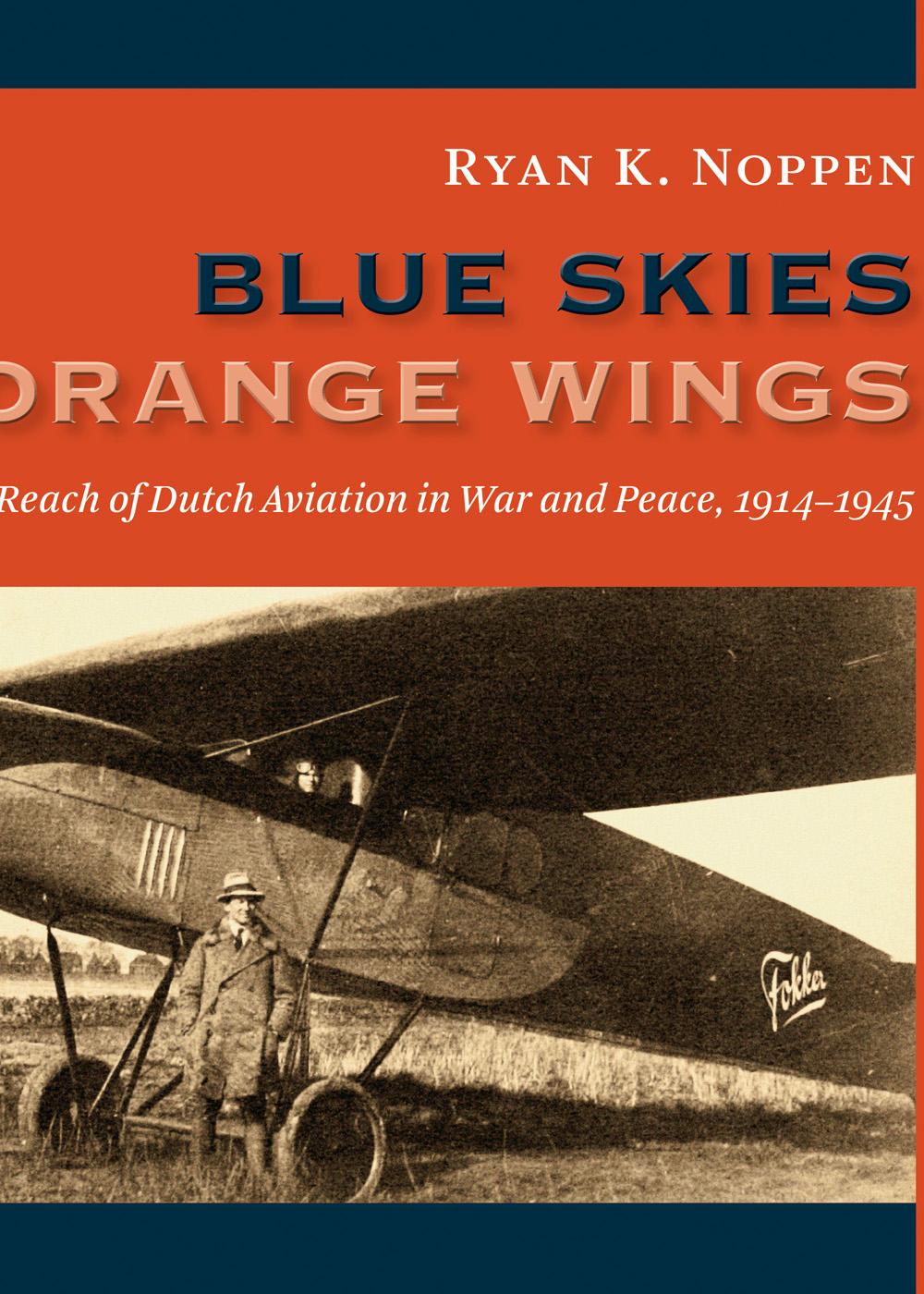

Starting the book in 2007, Noppen took a number of research trips to the Netherlands, Germany and Great Britain and stayed with relatives and friends there. It took him five years to finish the manuscript, and since then there has been work on tweaking the impressive volume, full of pictures, maps and profile drawings.

“My thesis is that the Dutch had a disproportionate impact on world aviation in the early days of flight,” he said. “For such a small nation to have the second largest airline, KLM, by 1939 is striking. In addition, the Fokker Company produced more airliners than anyone for a time. By the end of the ’20s, there were more Dutch-made airliners in the U.S. than those made by U.S. manufacturers.”

Anthony Fokker was a fascinating entrepreneur, eschewing academic theories and designing innovative aircraft through a hands-on workman-like approach, and Noppen follows his achievements in the book. Turned down by the British and French during World War I, Fokker made planes for the German military—one of them piloted by the famous “Red Baron” most Americans only know about in relationship to the Peanuts cartoon character Snoopy.

Noppen said KLM held to a modernizing imperative, seeking the best aircraft for its fleet, and was on the verge of commercial cross-Atlantic flights at the beginning of World War II. The Nazi invasion brought an abrupt halt to the Dutch rise in aviation prominence.

“For five days in May 1940, less than 200 Dutch warplanes were pitted against hundreds of German planes,” said Noppen. “The Dutch expected to be neutral, but once attacked put up an impressive fight; roughly four German planes were lost for every Dutch plane during the Battle of Holland.”

The Netherlands continued to have a domestic aviation industry after World War II, but its prewar prestige in aviation development was eclipsed, like that of most European nations, by the United States. However, Noppen believes the story of Dutch contributions to early commercial and military flight deserves increased acknowledgment in aviation history.

The book is full of rare photographs and fascinating stories of the planes and people who made such a prominent mark on world aviation.

And the Dutch reputation for aviation excellence does live on.

“In my opinion, KLM remains the model airline,” Noppen said. “Their planes and service continue to stand as the world standard.”