There are an estimated 100 billion stars in our galaxy. In any given year, none of them blow up.

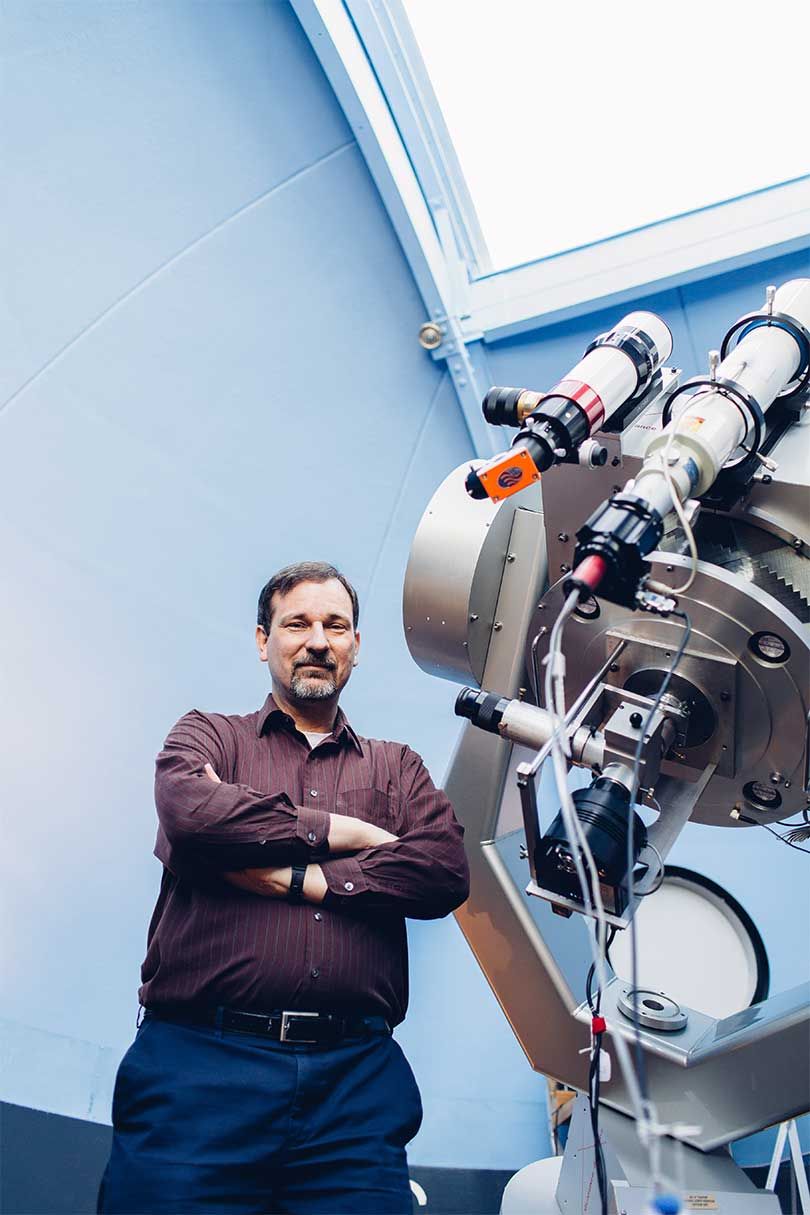

But an atypical year is coming very soon if Calvin astronomy professor Larry Molnar’s calculations are correct. Molnar is predicting that a star he is monitoring will explode between 2018 and 2020; a comparable prediction has never been made.

Update

January 6, 2017 - Read the latest updates on this developing story.

January 6, 2017

On Friday, January 6, the American Astronomical Society held a press conference during their annual meetings in Grapevine, Texas. There, Calvin College professor of astronomy Larry Molnar shared how the prediction he made in 2015 of a binary star merging in the near future is progressing from theory to reality.

Within hours of Molnar’s press conference, media from around the world had taken notice of the remarkable prediction. The news found its way through the scientific community through publications like Sky & Telescope, Astronomy Magazine and Popular Science, but also more mainstream outlets like National Geographic, The Washington Post, Forbes and USA Today. The news also quickly spread overseas being picked up by publications like The Telegraph (UK), RT (Russia) and The Indian Express (India).

And this discovery that has caught the world's attention started with a student's curiosity. The ABC and FOX affiliates in West Michigan highlighted 2014 Calvin grad Daniel Van Noord's significant role in the project.

“It’s a one-in-a-million chance that you can predict an explosion,” Molnar said of his bold prognostication. “It’s never been done before.”

The star known as KIC 9832227 came to Molnar’s attention in 2013. He was attending an astronomy conference when astronomer Karen Kinemuchi presented her study of the brightness changes of the star, which concluded with a question: Is it pulsing or is it a binary (two stars orbiting each other)?

Also present at the conference was then-student Daniel Van Noord ’14, Molnar’s research assistant. He took the question as a personal challenge and made some observations of the star with the Calvin observatory.

“He looked at how the color of the star correlated with brightness and determined it was definitely binary,” said Molnar. “In fact, he discovered it was actually a contact binary, in which the two stars share a common atmosphere, like two peanuts sharing a single shell.

“From there Dan figured out the orbital period from Kinemuchi’s data and was surprised to discover that the period was not the same as earlier data showed; it was getting shorter,” Molnar continued.

FURTHER EXPLORATION

Based on that discovery, Molnar and Van Noord wanted to explore further, so they continued to monitor the orbital period using the Calvin observatory. “We found the period getting even shorter at a faster rate,” said Molnar. They surmised that they might be seeing the merger of two stars, a process that can culminate in a kind of stellar explosion known as a Red Nova.

“It was really exciting to find something like this,” said Van Noord, who came to Calvin because of his interest in studying variable stars. While here he developed a now-internationally used computer program that discovers binary stars in archived data. “It’s proof that the method of research we use at Calvin works.”

The team also took cues from an article by astronomer Romuald Tylenda, who had studied the observational archives to see how another star (V1309 Scorpii) had behaved before it exploded unexpectedly and produced a red nova in 2008. The pre-explosion record of that star is the “Rosetta stone” that Molnar is using to interpret the new data.

“I remember thinking that if I ever see one [a trajectory] that looks like that, I better pay close attention,” said Molnar.

The Next Step

While the new star seemed to be following Tylenda’s model, other models and explanations had to be eliminated. This next step of research was taken by Calvin student Cara Alexander.

“We had to rule out the possibility of a third star,” said Alexander. “That would have been a pedestrian, boring explanation. I was processing data from two telescopes and obtained images that showed a signature of our star and no sign of a third star. Then we knew we were looking at the right thing.

“It took most of the summer to analyze the data, but it was so exciting. To be a part of this research, I don’t know any other place where I would get an opportunity like that; Calvin is an amazing place.”

Jason Smolinski, a Calvin professor collaborating on the project, said the research will produce results such that astronomers have never had before. “Any time stellar explosions are seen, it’s always after the fact,” he said. “That’s interesting, but you always wonder what was there beforehand? For us to be able to study this type of merger in great detail across the entire spectrum is remarkable,” he said.

Being a Christian astronomer gives you so much more wonder, it gives you so much more appreciation knowing that it was handcrafted–it was made by the hand of God. Cara Alexander '16

And Molnar is convinced Calvin is exactly the right place for a discovery of this magnitude.

“Most big scientific projects are done in enormous groups with thousands of people and billions of dollars,” he said. “This project is just the opposite. It’s been done using a small telescope, with one professor and a few students looking for something that is not likely.

“Nobody has ever predicted a nova explosion before. Why pay someone to do something that almost certainly won’t succeed? It’s a high-risk proposal. But at Calvin it’s only my risk, and I can use my work on interesting, open-ended questions to bring extra excitement into my classroom. Some projects still have an advantage when you don’t have as much time or money.”

“Being at Calvin gives you the freedom to explore,” added Alexander. “At large institutions you often study what you can get grants for instead of what needs to be studied.”

And it makes you more awestruck.

While Larry Molnar’s discovery is rare and atypical, the opportunity to document the finding along the way is an exceptional opportunity in its own right.

That’s why Sam Smartt, Calvin professor of communication arts and sciences, agreed to partner with Molnar to chronicle the process.

“I felt like it was a little gem of story here in our backyard,” said Smartt, who is a documentary film producer.

Smartt and others in his film production crew, including Kemp Lyons, Calvin’s video producer, and student Daniel Baas, have logged about 60 hours of filming. Smartt’s Intermediate Filmmaking class helped in the production of a trailer and a few short films this fall.

“I felt like we had to jump on it right away during the period of uncertainty—will it or won’t it explode?” said Smartt. “That’s what makes it interesting.”

The full documentary, which will continue to chronicle the research, will likely be finished a few years after the predicted explosion.

Luminous will focus on the nature of scientific discovery, the development of undergraduate researchers and the power of “small science.”

“Big science is multimillion dollar funding with a lot of people working on big projects,” said Smartt. “Small science is a small telescope with just a few people looking at one thing for a very long time. You wouldn’t think that a small liberal arts college with no graduate students and only an astronomy minor would have a story like this. It’s kind of an underdog story.”

So much wonder

“Being a Christian astronomer gives you so much more wonder,” she said. “It gives you so much more appreciation knowing that it was handcrafted—it was made by the hand of God. Secular institutions take the appreciation of the glory out of it. From the huge vastness to the tiniest of details, Calvin professors help you see it. They help you see God through it.”

With the star still following the model, Molnar is predicting the explosion will occur in about three to five years, at which time the star will increase its brightness ten thousand fold.

“If Larry’s prediction is correct, his project will demonstrate for the first time that astronomers can catch certain binary stars in the act of dying, and that they can track the last few years of a stellar death spiral up to the point of final, dramatic explosion,” said Matt Walhout, chair of Calvin’s physics and astronomy department.

Knowing God better is one of the things we seek to do. Larry Molnar

“The project is significant not only because of the scientific results, but also because it is likely to capture the imagination of people on the street,” he added. “If the prediction is correct, then for the first time in history, parents will be able to point to a dark spot in the sky and say, ‘Watch, kids, there’s a star hiding in there, but soon it’s going to light up.’”

Indeed, the explosion will catch the attention of scientists, media and ordinary people across the globe.

The outcome, one of the brighter stars in the heavens for a time, will be visible as part of the constellation Cygnus, and will add a star to the recognizable Northern Cross star pattern.

Molnar, who is now as certain of his prediction as science allows, believes whatever happens, “the answer will be interesting.”

“Knowing God better is one of the things we seek to do,” he said. “One of the ways to do that is to explore this amazing universe. The Psalmist says, ‘the heavens declare the glory of God,’” said Molnar. “If you’re not listening you’re missing that message.”