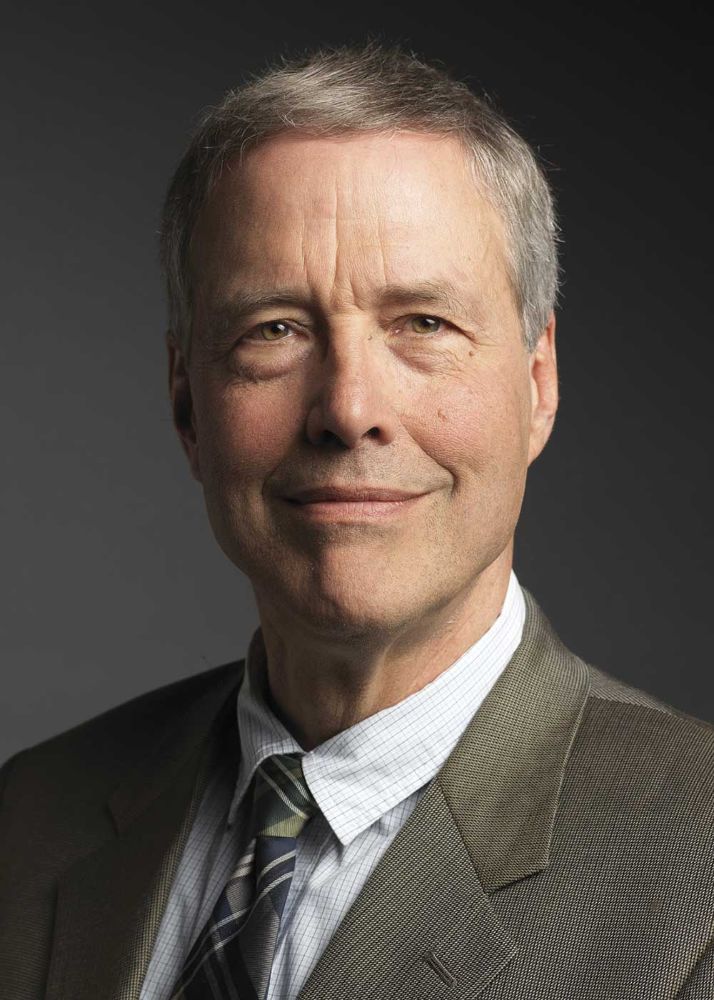

Spark recently talked with James Bratt ’71, Calvin history professor emeritus, about his new book, American Roots. It is scheduled to appear this summer as the latest entry in the Calvin Shorts series.

Why did you write this book?

I wanted to shed some historical light on the themes of conflict and diversity. Diversity is a major initiative at the college right now, as at many other institutions. And conflict—not least conflict over diversity—is particularly strong in American politics today.

So where are the “American Roots” of this syndrome?

Back at the start of the colonial era, from the founding of Jamestown in 1607 and continuing up to and sometimes beyond the American Revolution. Diversity most obviously involved the three main races on the scene—African, European and Native American. But it also involved the division of the original 13 colonies into five distinct regions. Each had its own geography and economy, its own mix of people, its own set of values, social expectations, and religious profile. The American nation started out as five mini-nations.

And when they came together, in trade or politics, they clashed?

They sure did. See the long slog of the War for Independence and the Constitutional Convention. Plus the legacies these regions bequeathed the future have shaped American politics and cultural clashes down to the present. But just as interesting, I think, are the clashes within each of these regions. Each section was programmed, as it were, to develop in a certain way, but it turns out there were tensions or contradictions built into the system.

One means of grace by which we can rise above [our circumstances] is learning the hows and whys of other people’s experience.James Bratt ’71

Some examples?

The most familiar is the Salem witch-craze in 1692. This was the hour of reckoning for the region of New England. It was built upon the values of tight cooperative communities living under the providence and law of God. When affliction descended—as it did in harsh measure for 15 years leading up to this episode—they carried out rites of repentance. When that didn’t help, they looked for internal “deviants” to blame. They found these right in their own prized families; they picked on aunts and grandmas. But each region had its own crisis. The colonies of the Lower South—the Carolinas and Georgia—were premised on slavery, so their trial came in the form of a slave insurrection outside of Charleston in 1739. For the Middle Colonies of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the moment of truth came in the American Revolution itself. This region was built on religion and ethnic diversity, but under pressure these groups turned on each other. The War for Independence became a civil war.

What can a non-American audience draw from this book?

I’m sure it offers some parallels to their own situation. The American colonies were an emerging society par excellence, with fragile political systems and multiple groups trying to find their way. And I think anyone can appreciate that their own people’s values and way of life harbor contradictions that need to be addressed—better earlier than later, when they’re ready to explode.

What wisdom

might Christians in general take away from this book?

For one, that Calvinism’s right (laughing). We truly are shaped by circumstances into which we’re born, and even as we try to move beyond them, we take them along. At the same time, one means of grace by which we can rise above them is learning the hows and whys of other people’s experience. I hope this history helps us do that regarding our neighbors, and ourselves.