Advent in the Northern Hemisphere is the season of deepening dark and encroaching cold. A primal dis-ease rises in many of us, triggering sometimes depression, sometimes a spiral of frenzied “holiday season” distraction. Animals respond to the dark and cold by taking in the threat, adapting to life as it is given. Thirteenth-century German mystic Meister Eckhart said, “Every single creature is full of God and is a book about God.” Each creature, like the woodchuck, shows us the Christ mystery at the heart of Advent: The dark is not an end, but a door. This is the way a new beginning comes.

WOODCHUCK Advent 16

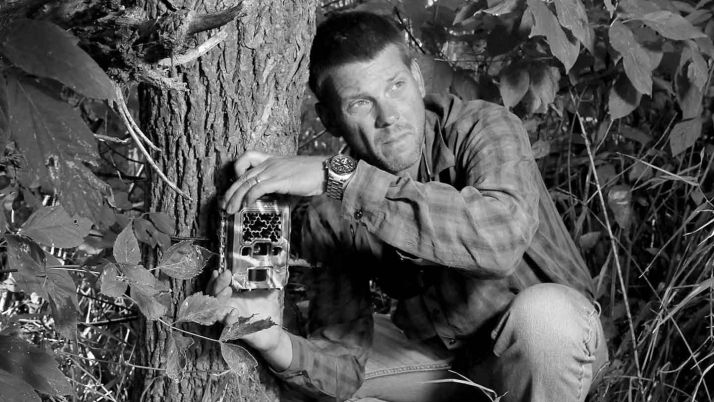

Knowing the complications below, I kneel in front of our garden shed and speak softly into the hole beneath its door: Sleep well chuck.

The hole plunges deeper than the frost line, then levels into a tunnel maybe as long as a three-story building is tall. At its end he’s tucked, head between his hind paws, in a room padded with grass and leaves. He might hear me—his ears are that sharp—if he’s awake. Certainly not if he’s asleep. Even if a predator could navigate that long tunnel and nab the sleeping woodchuck and shake him, drop him, bite him, the sleeper would sleep on, limp and insensible.

That’s not the threat. Deep in his burrow he’s safe from other mouths. It’s his own hunger he has to escape. Winter has wiped bare his vegetarian table. He would starve if he stayed awake. Asleep—a sleep so deep his heart barely beats and his body cools to nearly the temperature of ice—he expends almost no energy. Only at a glacial pace does he burn the fat he added eating up to three pounds of greens and fruit each lush day of summer. In deep sleep his hunger is subdued; his substance shrinks, but is not consumed.

And yet, he might be awake now, in the lean heart of Advent.

Whenever he sleeps, a finely calibrated inner clock ticks on. In abundant seasons it wakes him and sends him back to sleep on a predictable twenty-four-hour cycle. Now it lets him sink four, five, seven days down into a sleep so deep it amounts to self-absence. This both preserves him and stresses him mightily. At metabolic bottom, where sleep meets death, cellular sludge builds up, careful molecular balances tip . . . till his clock alarm rings, pulling him up, awake enough to use his toilet chamber and re-tune his body chemistry.

His inner clockwork also suffers the stress of absolute sleep. While he’s awake it recalibrates to ensure its alarm will wake him when his body chemistry turns precarious again in the next bout of sleep. Also, his clock and the clocks of all the area’s chucks recalibrate to stay entrained to a larger rhythm. No matter how long or short their individual cycles of wakefulness and sleep, the whole community is synchronized to a cycle of the earth itself and readied for a small window of opportunity.

Mid-February, the male under my shed and all his fellows will be waked, and this time crawl out of their burrows into the still barren world, looking for the homes of females. They will enter and acquaint themselves, males and females, but not mate. The window is not yet.

Their clocks send them back to their separate burrows to sleep again until the season’s final alarm signals, Now. Now is the time to mate, so that the kits-to-come will be weaned at just the moment when the world’s green food becomes abundant, so that they have every possible hour to eat and add weight before they must sleep, so that they will be stout enough to survive all the wakings of next winter. Then one spring day these young chucks too will wake into the ephemeral window and pass on the elegant rhythm that sustains them all.

Watch

Video creator: Hailey Jansson

Free Download

Download an excerpt of All Creation Waits (.pdf)

Text copyright © by Gayle Boss; Illustration copyright © by David G. Klein. Posted by permission of Paraclete Press, paracletepress.com.

Gayle Boss is a freelance writer, author and Calvin parent who lives on the edge of the Calvin Ecosystem Preserve.