On Monday, a friend who graduates this weekend asked me what the most difficult aspect of life after the Great Tassel Shift is. I had my answer immediately: The most challenging part of life beyond school is that it’s not about you anymore. If you grew up in a developed nation with compulsory public education and moderate-to-strict child labor laws, chances are the first 20-ish years of your life were entirely you-centric. Parents stowed your favorite sandwich in your lunchbox every morning, teachers dedicated tireless hours to Tetris-ing information into your brain, and politicians and pageant queens continually declared you “the future.” It seems, however, that this future is brighter for them than for us. For while they have the privilege of retiring or settling into mediocre acting careers, we are yanked from our adolescent incubators and thrust suddenly into a working world that is thoroughly and disconcertingly not about us.

And there is no sphere of society in which this education-to-occupation whiplash is more drastic than in schools.

A new teacher

As a new teacher, I’ll admit I often envy my students. I watch them flit between classes like Hogwarts firstyears, hear their accomplishments proclaimed in the daily announcements, and attend their plays, competitions and concerts. I salivate like a leashed child at a Golden Corral, remembering the tasty buffet of classes and extracurriculars lined up for me at that age. But as a teacher, I’m no longer a Golden Corral customer, but an employee who must wipe down the soft serve machine every half-hour. It’s frustrating to serve others when I still have such an appetite for personal betterment, and at times it has made my first year of teaching embittering.

A year out

But now, almost a year since graduation, the ache has diminished. This is partly because I’ve learned that investing in others and investing in myself are not mutually exclusive, but mostly because I’ve learned that if they were, the former would be a far more rewarding choice. For example, this spring I’ve volunteered as a coach for my school’s track and field team, and on Saturday, after months of my training with the kids and learning their quirks, we arrived at our regional competition. Our school had recently been dragged up to Division I, and the new standards were high. Hulking Rockford throwers tossed shot puts like snowballs, and Okemos sprinters launched from starting blocks so instantaneously I suspected premonition. Meanwhile, our small stride (the collective noun I’ve invented for distance runners) quivered nervously.

One athlete in particular appeared burdened by her hopes of qualifying for the state meet in the 800-meter run. Entering with a seed time of 2:29 and a 12th-place ranking, she would need either a 2:20 or a second-place finish to advance. The previous day after practice we had walked twice around the track together, visualizing her race and discussing strategy. So, by the time she finally toed the starting line, my hopes had so thoroughly meshed with hers that I teetered on the edge of my first panic attack.

Perfect execution

The gun popped, and the clock ticked. And as I zipped back and forth across the infield, I witnessed one of the most poetic things I’ve ever seen: Over the next couple minutes, she executed our plan to perfection, crossing the line in second place and a school-record time of 2:20. Immediately, I sprinted to the finish and found my athlete crumpled like a pop can, every iota of her energy spent. I haven’t felt happy or proud like I did in that moment for years.

Today, we had another track meet — an informal invitational that really doesn’t matter. Unfortunately, I also had plans to attend my high school choir director’s final concert tonight and could only stay at the meet for one relay. As I prepared to leave, I felt an odd pooling of emotion. I considered how I was about to miss a couple of my athletes’ last races in a school uniform. Then I thought about my parents and grandparents coming to every single race, concert and production of my childhood. Then I felt overwhelmingly loved. I took a final look at my little stride of runners huddled under blankets or foam-rolling their calves then turned toward my car.

Investing in lives

At the end of the concert tonight, our director called up all the alumni in the audience to join the high school choir for the final two songs. The first was a folkloric romp replete with mandatory hoots and hollers, and it felt fantastic to be woven in with my past classmates under his direction again. The second was an arrangement of “The Lord Bless You and Keep You,” sung at the end of every Chamber Chorale concert. Before we began, our director asked us to spread into the aisles and hold the hands of the choir members at our sides. As we sang the velvety words of the hymn, I watched our director and felt almost intimidated by the finality of 38 years of teaching— continuously investing in the lives and voices of others—about to resolve in a single note. I watched his snowy blue eyes drift slowly over us with practiced satisfaction as we cascaded into the final “Amen” and, for the first time, thought I might have a small taste of what he was feeling.

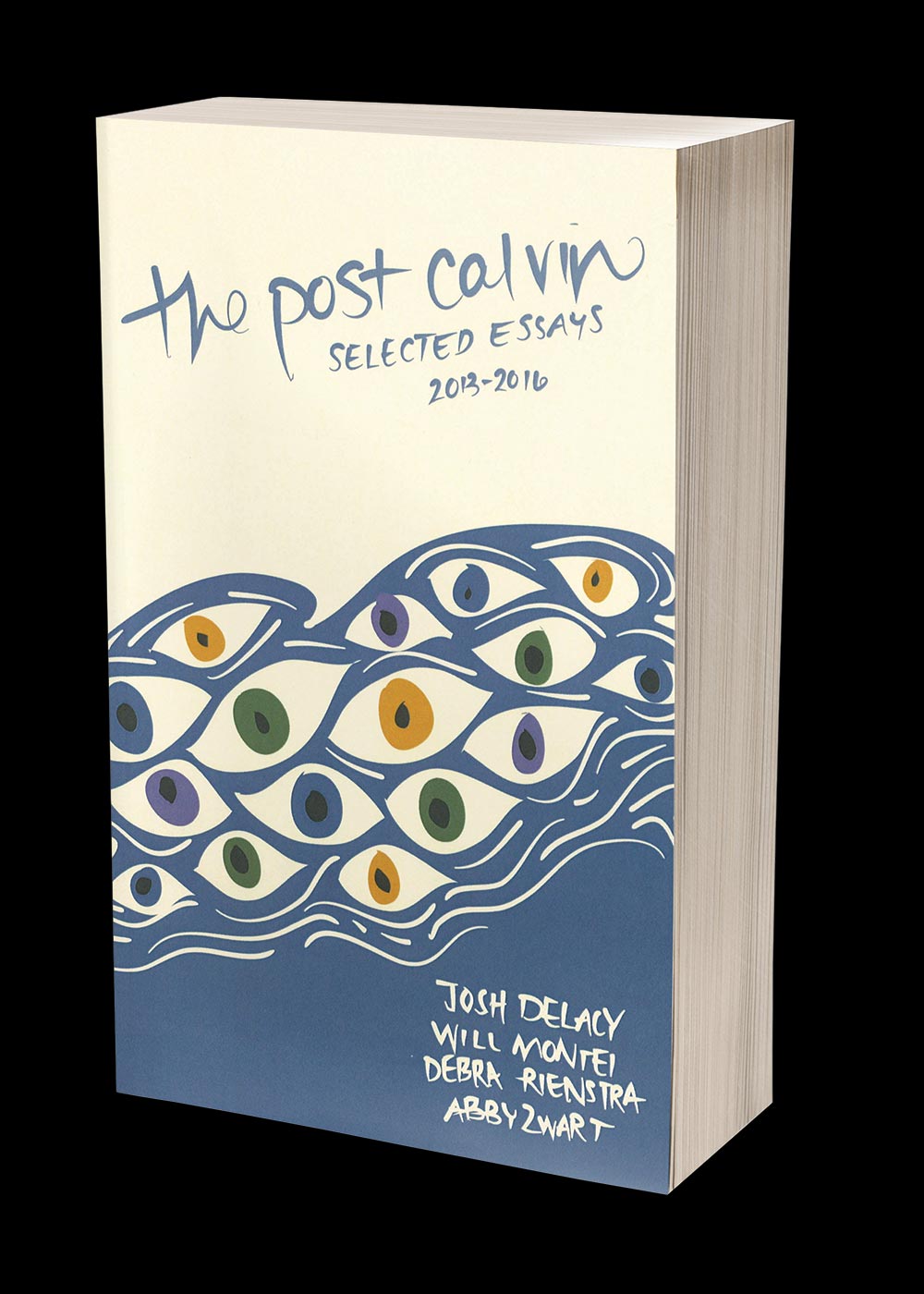

The post calvin: selected essays gets intimate with 20-something life. Forty-four Calvin alumni share their experiences of faith, purpose and love through a variety of topics ranging from social justice to travel to food. Illustrated by Maria Smilde ‘14, The Post Calvin: Selected Essays shows the breadth and depth of that often-misunderstood decade after college. It’s a book that takes craft seriously and takes honest engagement with post-diploma life even more seriously.

The book is available at the Calvin College Campus Store: $26.99 (hardcover), $13.99 (paperback).

Buy it today