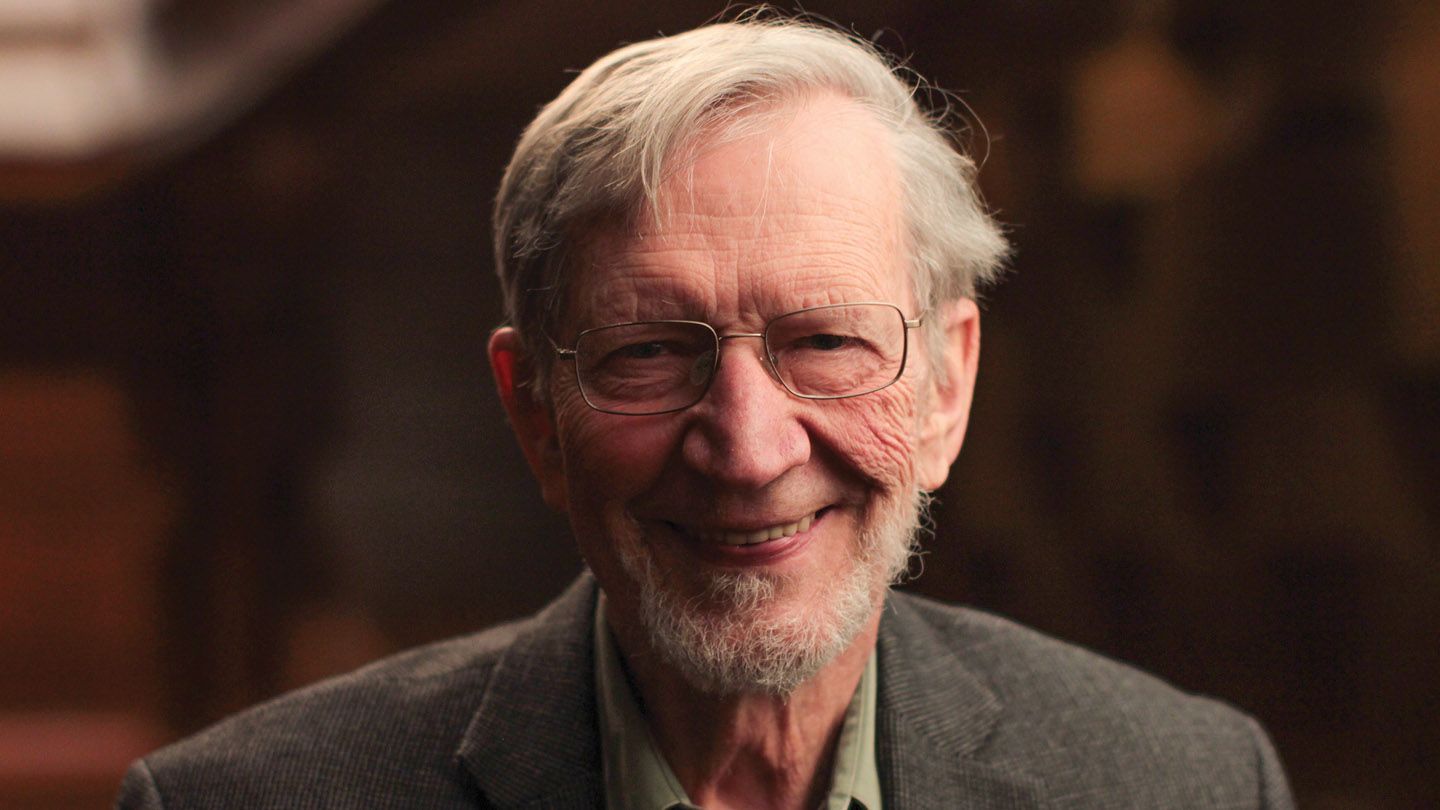

Alvin Plantinga '54 is an American scholar whose rigorous writings over a half century have made theism—the belief in a divine reality or god—a serious option within academic philosophy. He was announced in April as the 2017 Templeton Prize laureate. The Templeton Prize, valued at $1.4 million, is one of the world’s largest annual awards given to an individual and honors a living person who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension, whether through insight, discovery or practical works. Plantinga joins an esteemed group of 46 prize recipients, including Mother Teresa, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama. On Sept. 24, 2017, Plantinga will be formally honored at a celebration held at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Plantinga, while considered a giant in philosophical circles today, started his revolutionizing journey as a teenager reading Plato. We sat down with Al this summer to discuss his six-decade journey in the field, what sparked his interest in the intersection of philosophy and Christianity, and his advice for the next generation of Christian philosophers.

“Al Plantinga’s work has changed the terrain of philosophy and even the academy more broadly. He has shifted the plausibility conditions of academic discourse, making room for faith in the halls of the university. An entire generation of us have become Christian philosophers because of his example and encouragement.”

James K.A. Smith,

professor of philosophy, Calvin College

How did you get interested in philosophy as a young person?

My dad was a professor of philosophy. And when I was 13 or 14 I started reading Plato’s dialogues and talking about them with my dad. I guess my interest in philosophy just grew naturally.

How did you develop a passion for Christianity and philosophy?

I was brought up as a Christian, then when I got to be 15 or 16 there was an awakening … . I became much more serious about Christianity. My father was a professor of philosophy at Jamestown College. During my freshman year I went to Jamestown College for one semester. Then my Dad moved to Calvin. I moved with him and went to Calvin for one semester. Then the next year I went to Harvard for one year and I liked Harvard a lot. But while I was at Harvard, during the spring vacation, I came back to Calvin and visited my parents and heard Harry Jellema lecture three times that week in a class on ethics, and I was so impressed with Harry Jellema that I left Harvard and came back to Calvin.

“Plantinga’s influence has come both through his books and many articles and through his teaching and public lecturing. Hundreds of graduate and undergraduate students have found his teaching compelling and inspiring. His public lectures have regularly drawn hundreds. On a recent lecture trip in Iran he was hailed as a rock star. He has ‘presence.’”

Nicholas Wolterstorff,

Former colleague of Plantinga at Calvin College

How was it that you came to a point where you said, “I want to figure out a way Christianity and philosophy could be compatible?”

The idea that Christianity and philosophy are like oil and water and can’t mix never occurred to me until after I had left Calvin and then I heard it from other people who felt that way. It’s not like I had to overcome that, I didn’t even hear of it until I was out of college.

How would you define your calling?

My idea was that my job was to be a Christian philosopher and to interest as many people as I could in being a Christian philosopher and defend the whole idea of being a Christian philosopher. While at Calvin it wasn’t a problem like it was in the philosophical world at large, where one idea was you couldn’t seriously be both a real philosopher and a serious Christian.

Templeton said your ideas revolutionized the way we think. What do you think they meant by that?

I think bringing philosophy and Christianity together to be an unabashed Christian in philosophy is what they had in mind … . I’ve met many philosophers who are Christians but were very low key about it, sort of keeping their head down. That wasn’t true of me, but not because I was especially brave or anything, but because of the places where I was teaching at where being a Christian was of course absolutely acceptable.

I’d like to encourage young Christian philosophers and college graduates and the like to see Christian philosophy as what it is, something very important for the Christian community, something really worth working hard at, and something to be proud of.

Alvin Plantinga

Did you know the ideas you were dealing with would be revolutionary?

No, I never thought of them as revolutionary … . What might have been unusual was that I talked about Christianity as a philosopher without being embarrassed or ashamed or soft-pedaling it or thinking I was a second-class citizen because of that or worrying about philosophers who wouldn’t approve of it. I didn’t really worry about what they would think; I just did what I thought was the right thing to do.

What are the pressing issues in philosophy that need a Christian perspective?

I don’t know if there’s anything that’s really new. There are materialist philosophers; there are Christian philosophers; there are humanist philosophers; and the Christian philosopher’s job now—which it has been and I think it will be the same in the future—is to represent Christianity in an unabashed, unafraid way against these other currents in philosophy.

A selection of books by Alvin Plantinga

- God and Other Minds: A Study of the Rational Justification of Belief in God

- Cornell University Press, 1967

- This work, a potent defense of the rationality of religious belief, is widely acknowledged as having put theistic belief back on the philosophical agenda.

- God, Freedom, and Evil

- Eerdmans Publishing, 1974

- “Alvin Plantinga’s free will defense” is almost universally recognized as having laid to rest the logical problem of evil against theism.

- Warranted Christian Belief

- Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000

- The third book in Plantinga’s “Warrant Trilogy” based on his 1987-88 Gifford Lectures is widely hailed as one of the most important philosophical treatises on religious belief published in the 20th century.

- Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism

- Oxford University Press, 2011

- This book was a long-awaited statement on the compatibility of science and religion. The real conflict, Plantinga concludes, is not between science and religion but between theism and naturalism—theism supports science, while naturalism undermines it.