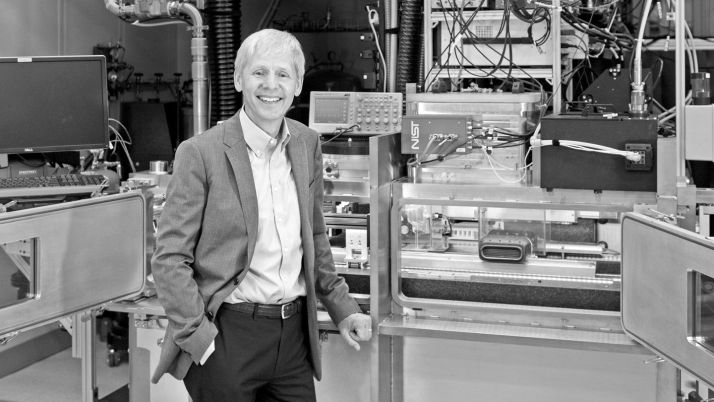

Tuesday, May 10, 1994. Jonathan Niehof ’00 distinctly remembers that day, specifically its partial solar eclipse. “I brought filters and pinhole cameras to school so other kids could watch it with me,” he said.

He had no idea that 25 years later he’d still be helping people look at the sun.

Niehof is part of a team that’s helping send NASA’s Parker Solar Probe closer to the sun than any human-made object has ever come. Launched in August, the spacecraft made its first flyby in early November. In 24 orbits over seven years, it will eventually come within 3.7 million miles of the surface. That’s one-eighth of the distance between the sun and Mercury, its nearest planet.

“This is real discovery stuff,” Niehof said. “The data is so unprecedented, we don’t even know what to expect.”

Parker Solar Probe is designed to study three big questions in solar physics. Niehof, a research scientist at the University of New Hampshire Space Science Center (UNSSC), is working on the third: How do some of the sun’s most energetic particles rocket away from the sun at more than half the speed of light? UNSSC is operations headquarters for two instruments onboard the probe that measure high-energy particles.

It’s that last question that engrosses Niehof. The UNSCC is the operations headquarters for two instruments on board the probe that measure high-energy particles. “These energetic particles get a good acceleration kick right out of the sun,” Niehof explained. “But as they move out through the solar wind, they’re changed. We want to work out the physics of the change all the way from the sun to the Earth. Then, if we see something on the surface of the sun, we’ll be able to predict what the radiation environment will be like on Earth a few days later. Because these particles can cause severe radiation damage to spacecraft, and the magnetic field carried in the solar wind can disrupt satellite electronics.”

A physicist and a computer scientist, Niehof’s specific role in this mission is to take the raw, compressed data collected by the probe’s energetic particle instruments and refine them into a form that scientists can use. He expects the first download of probe data in late April.

“Baseline, my job is to make sure this data is available for everyone—including, ultimately, the public. But I’m definitely part of the everyone who wants to sink my teeth into it!”