- Friday, January 5, 2018

- 8:00 PM–10:00 PM

- Covenant Fine Arts Center

- FREE

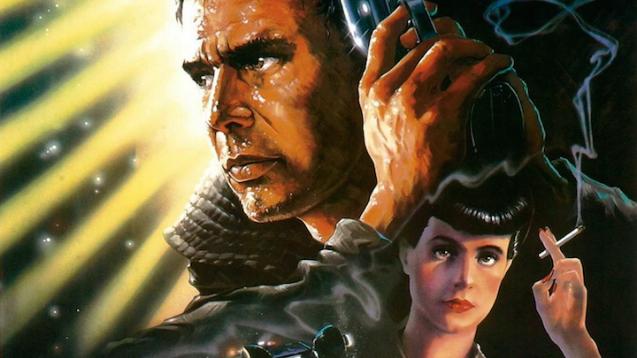

In anticipation of showing Blade Runner 2049 the day after!

"When "Blade Runner" premiered in 1982, Harrison Ford disparagingly quipped, "It's a film about whether you can have a meaningful relationship with your toaster." It is, in fact, an amazingly sophisticated, sumptuously visionary treatise on the consequences of attaining god-hood. The toaster, in this case, was actually a genetically engineered "replicant" -- vulgarly known as a skin job -- played by a radiant Sean Young. And as Ford found out, the answer is, yes, as long as you know how to turn that appliance on.

The eyeball-popping thriller was "Alien" director Ridley Scott's first American film, a box-office disappointment lost on audiences appalled by the British visualist's glowering, smoggy portrait of the future. Critics, many of them anyhow, reviled it for the drone of Ford's voice-over narration and the upbeat Hollywood ending, but the film persevered. Now Scott has recut the movie, and it's back on the big screen. The director has deleted the narration (added against his and Ford's wishes) and the tacked-on coda (those swooping scenes are actually leftover footage from Stanley Kubrick's "The Shining"). Freed of these distractions, "Blade Runner" becomes a purer pleasure.

Scott, a provocative visual stylist, brought terms like cyberpunk and retrofitting into the American vocabulary with this voluptuously decadent, sensor-overloaded portrait of Los Angeles as it might be in 2019: crowded, polluted, clangorous, damp, desperate and diverse. Patrol cars called Spinners carom through the canyons created by skyscrapers 400 stories tall and crumbling in the acid rain. Millions have migrated to off-world colonies, the spacious glories of which are incessantly touted by blimpy flying billboards. The rainbow billions left behind squeeze through the jammed, littered, neon-splattered streets as numb to hope as they are to the noise.

The screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples strays far from its inspiration: Philip K. Dick's "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?," the tale of a genetic designer, Sebastian (William J. Anderson). Sebastian plays a pivotal role here too, but the focus is on Rick Deckard, a retired detective who specializes in tracking down and destroying replicants who attempt to pass for human. Stronger and more specialized than real people, the replicants are sent off-world as slave laborers, soldiers and prostitutes.

Deckard, the best blade runner ever, is pressed into duty by his former boss (M. Emmet Walsh) when four replicants take over a space shuttle and return to Earth. They have come back, as their leader Roy Blatty (Rutger Hauer) explains, to meet their maker, Tyrell (Joe Turkel). To keep them from supplanting the men who made them, replicants have a built-in fail-safe -- a four-year lifespan -- and they've decided to discuss it with their man upstairs. "What seems to be the problem?" asks Tyrell. "Death," responds Roy, ever the wry, cerebral psychotic.

Grand enough in scale to carry its many Biblical and mythological references, "Blade Runner" never feels heavy or pretentious -- only more and more engrossing with each viewing. It helps, too, that it works as pure entertainment. In its soul, it's a detective story complete with a glossy dame and a Chandler-style gumshoe suffering from a case of hard-boiled heartburn. Like Bogey before him, Deckard must shake off the troubles he's seen, the numbing shell, to get back in touch with his feelings. He becomes human again thanks primarily to the replicants who are driven by love for one another to develop empathy.

Scott has enhanced the love relationships somewhat, adding and lengthening scenes between Rachel (Young) and Deckard and between the pleasure model Priss (Daryl Hannah) and her lover Roy. Hannah and Joanna Cassidy, the snake dancing replicant, aren't quite as resilient as Lt. Ripley in "Alien," but we see their moxie reiterated in the heroines of Scott's 1991 road movie, "Thelma & Louise," the 1989 thriller "Someone to Watch Over Me" and the saucy hussies in his Chanel perfume advertisements.

The filmmaker also has expanded on the unicorn references, which he says "provoke Deckard's doubts in his own essence." The blade runner has just confronted Rachel with the fact that her memories are not really hers, but implants borrowed from Tyrell's niece. When she storms out of his home -- Frank Lloyd Wright's Ennis Brown house -- Deckard gets out the family album, no longer sure of his own past. There's also his sidekick, police lieutenant Gaff, and his origami animals -- a unicorn, a stick man and a chicken among them -- which serve as a running commentary on the evolution of Deckard's character.

Gaff (Edward James Olmos) is an interesting specimen, which may not be as evident on video versions of the film. He's a walking melting pot with blue irises in his almond-shaped eyes and pocked Asian skin weakened by the filthy air and stress of living in the 21st century. He speaks a patois of Japanese, Spanish and English, a language that reflects the true, and as it has turned out prophetic, ethnic makeup of the City of Angels.

Every viewing of "Blade Runner" brings new discoveries -- a half-midget, half-mechanical toy's decidedly sexual response to Priss's appearance in Sebastian's living-doll-filled apartment -- and revitalizes treasured visual memories -- the way Rachel's copper irises give away her kinship to Tyrell's synthetic owl. Of course, those who've seen it only on video really haven't seen it at all. Just the shadow."

—Rita Kempley, Washington Post