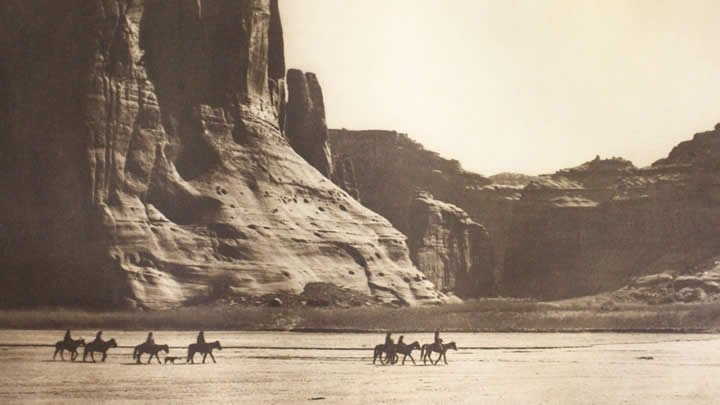

Canon De Chelly - Navaho, one of Edward Sheriff Curtis' photogravures.

Calvin’s Center Art Gallery is honoring Native American History Month with “Tracing the Past: Edward Curtis and The North American Indian,” an exhibition that brings together Native American historical artifacts and the work of early 20th century photographer and amateur anthropologist Edward Curtis.

From Oct. 30 to Dec. 20, the gallery will display 40 of Curtis’ original photographs from his collection on “The North American Indian” alongside 24 Native American artifacts similar to those represented in the pictures. The exhibition is sponsored by The Mellema Program in Western American Studies.

Connecting pictures and artifacts

The artifacts, which are on loan from the Grand Rapids Public Museum, range from spoons, to hats to snow goggles—all of them from the same time period as the photos that accompany them.

“When you look at a hat [in the exhibition], you’re looking at the same kind of hat from the same time period as the hat the person in the picture next to it is wearing,” said Joel Zwart, the director of exhibitions at Calvin College. “I wanted there to be that connectivity in the exhibition.”

Although the exhibition only features 40 photos between 1906 and 1936, Curtis took more than 800 photogravures of Native Americans in the western United States. He released the photos in a series of bound books to subscribers, one of which happened to be Muskegon's Hackley Public Library. The set is now housed at the Muskegon Museum of Art, which lent Calvin the photos for the exhibition.

Documenting Native Americans

The expansive series was Curtis’s attempt at documenting what he saw as a dying way of life.

“Curtis believed Native American ways of life could not transition into the modern world and were fated to disappear,” explained Calvin history professor William Katerberg. “He admired their way of life and began this project because he wanted to document it before it disappeared.”

Scholars still debate whether Curtis’s documentation effort was successful.

“There is skepticism because a lot of [Curtis’ work] was in some ways contrived. If Curtis did a portrait of a native, he wanted them to be in their Native American clothing, and he was going to pose them in certain ways to fit into his idea of what a Native American should be,” Zwart said.

A man of his time

However, Zwart emphasizes that Curtis was a product of his time:

“He was working in the confines of his time period. His intentions were good, even though what he presents is an image he wanted to portray of Natives, not the reality.”

Katerberg adds that some Native Americans actually helped Curtis with the project:

“[We shouldn’t] ignore the role of the Native Americans involved in his project. Curtis depended on Native assistants, who visited local communities before he arrived, helping him establish a relationship with local people. And local Native people often had their own reasons for allowing Curtis to photograph them.”

Continuing the discussion

In conjunction with the exhibition, Katerberg and Calvin art history professor Elizabeth VanArragon will discuss the historical context and documentary accuracy of Curtis’s work in a lecture at 7 p.m. on Nov. 7 in the Covenant Fine Arts Center Recital Hall.

“Curtis is part of a long history of artists that did paintings and later photography of Native Americans, who romanticized Native Americans as Noble Savages, seeing them as naturally uncorrupted and living harmoniously with land, in contrast to civilized people no longer living naturally,” said Katerberg. “In the lecture, I’m putting Curtis’s work in that context.”

The lecture is one of four programs planned in conjunction with the exhibition. William Wilson, who grew up in the Navaho Nation, will be speaking in the Recital Hall at 7 p.m. on Nov. 21 about his attempts to continue Curtis' documentary efforts. There will also be showings of the films “Reel Injun” and “More Than Frybread.”

Important conversations

Calvin economics professor Becky Haney sees these events as opportunities for discussion about the challenges Native Americans face today.

“Thinking about the ways Curtis’ work led to more wellbeing among Native Americans and the ways it contributed to their challenges is a great way to open up conversation about Native American identity today,” she said.

Haney knows from personal experience how valuable that dialogue can be. Before she came to Calvin, Haney ministered in a predominately Native American community, where she was one of just two non-Native American pastors in her classis. She is also married to a Native American and is active in the Grand Rapids-area Native community.

Connecting to the community

“I have been able to have rich, generative, meaningful conversations with people who have experienced a different reality than me,” she reflected. “That’s allowed me to see more of how God is working in the world, and to see the sources of injustice in our societal structures. I’ve also seen the ways I contribute to that through denial and what I might do differently.”

Haney hopes to use her connections to the Native community to organize opportunities for further dialogue between Calvin students and Native Americans.

As part of that effort, later this year, she will be leading a walking tour for both students and area Native Americans of the Native American sites in the Grand Rapids area.