A constant reminder

Excerpts from the Fall 2005 Faculty Conference Address

Barbara Carvill, Professor Emeritus of German

When I was hired at Calvin College 27 years ago, new faculty members were often asked at their board interview three questions.

- Do you know the image and origin of Calvin’s emblem?

- Do you know the Latin motto and its English translation?

- What do you know about the origin of these words?

The second question will not be asked any longer, because during Calvin’s own Vatican II in the 1990s, the Latin text was replaced by the English translation:

The Latin seal is used only for most official purposes—such as for a presidential visit:1

The answer to the first question is easy: it is a hand holding out a heart. And your guess is correct that its origin has something to do with the Reformer John Calvin. Indeed, John Calvin, during his second stay at Geneva, used the image of a hand and a heart for sealing his letters in the 1540s as you can see, naturally without any motto:2

You will agree with me that as graphic design this looks somewhat clumsy. On this seal from 1545, the hand holds something that looks like a butterfly or maybe a tulip and thus prophetically summarizing our Reformed theology.

On the seal from 1547, the hand is turned around and holds the heart which may slip any moment out of its loose grip in a way that reminds us more of a card trick. Just the initials J and C—either John Calvin or Jesus Christ or both-frame a code of arms; there is no other text.

The first rendition with only the motto prompte et sincere appeared in 1566 on this portrait made two years after Calvin’s death.3

You see a quite realistically drawn hand with spread out fingers holding a three-dimensional heart in a rather unconvincing way. The heart seems to have been stuck into a hand without the hand knowing about it; otherwise the fingers would not be so open.

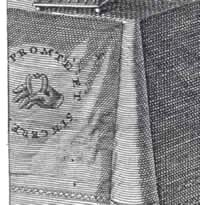

In a Dutch engraving 130 years later, hand and heart appear again, this time on a table cloth.4

This too, is a bit awkward: the heart here looks to me more like an apple, a tomato, or rather like two small linked sausages—actually like the world’s best bratwurst you will only find in Nürnberg, Germany, not far from where I grew up.

In the 1910 yearbook of “De Theologische School en Calvin College ,” appeared for the first time a picture of what was later to become Calvin’s emblem. As you can see, it follows closely John Calvin’s seal, with its slipping heart now more in the middle of the hand, the initials JC, this time framed by a Latin text and set in a church window. J-C now has acquired a third meaning: Junior College. “Onze school voor onze kinderen ”!

20 years later we have a similar rendition without this window.

Due to the persistence of the students who were pestering the faculty and board for years to adopt an official emblem for their school and, above all, one for their school ring, finally, more than 50 years after the founding of our institution, the symbol of the open hand and heart became finally the official logo. But it took many heated faculty meetings—mainly because some members of the faculty found the seal to be simply “unaesthetic.” 5

The new official insignia of the college appeared for the first time in the Chimes of January 1933.

Notice some major changes: The initials JC are gone. The hand does not any longer hand over the heart horizontally to some invisible recipient out of the picture, but the heart is set into a graceful open hand and presented upward, a heart offered to heaven, to God.

The new shape was not, as the Chimes article of 1933 says,“changed somewhat to conform to our modern standards of art,”6 but instead

was inspired by a 17th century coin commemorating John Calvin.7

I paraphrase the motto: [he did his] work for the Lord willingly and in singleness of mind.” The mood is triumphant and visionary, and lacks completely the awkwardness of the hands and hearts we have seen so far. Nothing is timid or clumsy or humble: A strong open hand coming out of a cloud presents a pristine three dimensional heart to the divine light of the sun. My sense is that this coin celebrates John Calvin’s heart in its glory, redeemed and reshaped by Christ and presented confidently to the majesty of God.

The 17th century artist who designed this coin followed a pre-reformational iconographic tradition which points to Saint Augustine who is often represented holding a heart in this way.8

I have said already, the hand on our college’s emblem from 1933 is holding the glorified, redeemed heart from the coin.

Needless to say, as a graphic design, this is more felicitous than the hearts on John Calvin’s letter seals. Although hand and heart have lost their baroque fleshiness, are two dimensional again, and are somewhat squeezed into a restricting code of arms frame, the whole image projects confidence, assurance, and optimism. I see in this change a shift in confessional emphasis. Now we seem to be saying: We know for sure that what we offer to our Lord as a sacrifice, God will, by God’s grace, consecrate, reshape, and redeem.

However, we ought not to forget the iconographic precursors of the emblem. When we follow the example of the motto and offer our hearts to God through our academic and administrative work, these hearts may not look like the one on the coin. Our hearts come in all kinds and shapes, large and small, with defects, damaged, and broken, unaesthetic, and some may even look like tomatoes or sausages. And if we are honest with ourselves, we offer these sinful hearts in a stumbling, painfully awkward way, and often without the confident assurance of our present logo.

So, dear friends, when during those dark hours in the semester you look at the pure, redeemed heart of our emblem and you look into your own heart and ask yourself, “What am I really doing here? Does it amount to anything? Do I actually educate my students for shalom? Do I really equip them to be agents of reconciliation and renewal?” Then, don’t lose heart. Continue, pray, and do your best, and know that God does accept and bless your modest, clumsy, bungling, misshapen heart work and that, through Christ, that heart offering is redeemed and made beautiful. John Calvin, a modest and very humble man, professed this attitude on his seals. He knew that the heart he offers to the Lord is a sacrifice to God in need of Christ’s redemptive love. For this reason he surrounded it with the initials of God’s son.

On the other hand, if we congratulate ourselves proudly for being such a great, Harvard-like, academy and gloat in the success of our scholarly and institutional work, it is good to look at our logo and its precursors and write the JC around the heart again.

What directive, then, do the Calvin College logo and its iconographic history give us on our journey through the year? Work wholeheartedly for the Lord, but be humble and have faith.

We can learn one more moral lesson by looking at the changes that the frame around the central image has undergone in the last 100 years: The heart, the hand, and the motto started out being completely framed and embedded by the church, whereas today, the text is no longer contained by any framing line and the letters spill out into space.

Allow me to over-interpret the meaning of this graphic development: Calvin College today is a Christian academic institution that educates the next generation for service not only to the church, but to all of society, to all nations, and to the whole world. It says to us faculty and administrators, don’t hide in your provincial comfortable Christian nest, go out, be bold, think big, look outward, or, in Joel Carpenter’s words from last year’s faculty conference address, be “agents of the Great Commission.”9

And that same openness at the margins says: we want to be a welcoming, inviting, and hospitable community, come and join us!

Talking from my personal perspective, I have experienced this college as such a welcoming, hospitable place. When I look back, I am deeply grateful to God that my department, the administration, and the academic community have welcomed me, an outsider, a German Lutheran to boot, and given me a place where I could develop and give my best and where I always was encouraged, appreciated, and supported. I hope very much for the new faculty and staff that you will experience this academic community in a similar way.

So, after having done a kind of spiritual exegesis of the Calvin icon, I say to you, at the beginning of your journey through the semester: be humble and look outward, be hospitable!

I will not elaborate on the interesting origin of the motto on Calvin’s emblem,10 but I need to say one more thing about its central message. To offer someone your heart is really a love declaration. A love declaration to God. We do our work to show God our love so that God can delight in us teachers, our scholarly work, in our students and the Calvin community.

So, I say to you for your journey: Take heart and teach with all of your heart. Teaching from the heart means teaching from your spiritual center. Share freely with your students what drew you to your discipline and why you love what you teach and research. Love is contagious. Be humble, teach without arrogance and stop being impressed by and in love with your own unquestionable intelligence, your scholarly production, and your pedagogical savvy. Be patient and don’t blame students. Think hard about and find fresh ways to deepen the faith of your students through the way you present the subject matter.

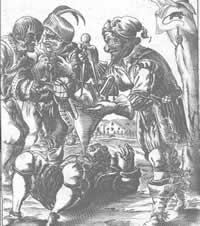

Let me illustrate what I am saying by showing you two images from the past which have to do with teaching.

© Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg

The first is a satirical broad sheet engraving from the 17th century.11 It shows the Nürnberger Trichter, the Nuremberg Funnel, as it was called, in action. Some quack educators are busy stuffing the student full with the subjects of the liberal arts curriculum of the day—the septem artes liberales. The material does not really fit into the funnel, and to get it into its narrow pipe assumes colossal effort on the part of the teacher and a high tolerance of pain on the part of the learner who has to endure such an act of invasive educational violence. The student is a helpless victim force-fed by his educators and reduced to a kind of garbage receptacle for dead learning.

Although this is a satire of bad teaching from the 17th century, this kind of education is still with us. In his 2004 book on What the Best College Teachers Do12—a book a group of Calvin profs studied during the summer—Ken Bain talks about “bulimic education”13 where learners are force-fed and where instructors expect “the regurgitation of facts and the subsequent purging.” Clearly, this kind of teaching and learning bypasses the heart and is heartless.

Yet, the food metaphor for education does have some value. We can think of our teaching as offering hospitable meals we prepare for our honored guests, our students, something they can chew on and that nourishes their mind, their hearts, and their faith. “Good teaching,” Parker Palmer says, “is to create a hospitable place.” Sometimes we have a banquet prepared for the students, sometimes it is potluck and they have to bring their own to the table. Sometimes you know that what you have cooked up is fast, cheap food and sometimes all you bring to class is stale leftovers.

During one of our discussions of Bain’s book I just mentioned, faculty members were asked to share their last thoughts in the hallway just before entering the class rooms. One faculty member, whose name I need to divulge, because every speech of historic importance has to mention this name—so, Jim Vanden Bosch said something very profound in this context: He said he goes into his class with the question: “How many of my students will I let down today?”

I was struck by this, because it says to me three things: it says that it is so much wiser not to go into class full of yourself and ego-driven. It says that we must be realistic and aware of our limited effectiveness as educators, but it also says to me that this awareness opens our hearts for the students we let down and, hopefully, pushes us to find ways, the next time, to serve and challenge them better.

Perhaps the following early 14th century wood sculpture from Southern Germany gives a more heart-and mindful model of teaching than the Nuremberg funnel. No, it is not a medieval kindergarten teacher—it is—and English 101 or foreign language instructors will appreciate this especially—it is the figure of Grammatica, of Grammar, one of the seven liberal arts.14

© Bayerisches Nationalmuseum München

Normally, Grammatica is portrayed as a woman wielding a stick or some other rod for beating the grammatical rules into the pupils. Not on our picture.

Grammar does have some kind of club or cane under her arm but cannot use it, because instead of hitting the boy on her left with it, who seems to be uninterested in the subject matter, she ever so gently keeps hand contact with him and nudges him along, patiently and full of confidence that one day he will move his head around and be “with it.” And the good eager student on her left is reaching out for her, he stretches his mind and wants to know so much and is aware of how much he still has to learn. I suggest we have here a picture of a teacher who shows confidence, humility, authority, gentleness, sure guidance, and a generous heart.

I have come to the end of my talk. Let me summarize the good words for our journey ahead of us we gleaned from looking at some images: Be mindful, be humble, look outward, be hospitable, and teach from your heart.

There will be times in the coming months when we race around in this place feeling exhausted, when we find no time to talk to anybody or pray with colleagues, no time to go to chapel, to have lunch with faculty, no time for scholarship, exercise, no time for our families and friends in short, there will be times when a grinning devil rubs his hands in glee over this Christian college, so when these times come, think about our tagline and the college emblem and let’s re-mind each other to be mindful and to be humble, to look outward, to be hospitable, and to teach from the heart.

1.Not everyone is happy with the translation of “prompte” with “promptly.” Rich Wevers, professor of Classics emeritus at Calvin College, suggested that the heart offered to God does it “without hesitation,”“willingly” rather than “promptly.” I think ‘prompte’ echoes the willingness of the spirit as in Matthew 26:41: “Spiritus quidem promptus est, caro autem infirma.” "Prompte" has to do with the disposition of the spirit and will within us and not so much with being on time and doing something right away without procrastinating, as the modern translation suggests. The Latin juxtaposition of "prompte et sincere" predates John Calvin. In Catherine of Sienna, for example, "prompte et sincere" is the description of her offering of obedience to God and her spiritual superior in her “De Obediencia.” The juxtaposition of "prompte and sincere" appears in other prereformational texts to qualify obedience. Examples can be found in Tertullian and Aquinas. I would like to express here my gratitude for the help I received for this part of my paper from Paul Fields at the Meeter Center for Calvin Studies and Robert Sweetman from the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto.

2. Cf. Marcel Cadix, “Le calvinisme et l’expérience religieuse”, in Société de l’histoire du protestantisme français, 84 (1935) p.172.

3. E. Doumergue, Iconographie Calvinienne , Lausanne : George Bridel, 1909. p. 66, Pl.XV.

4. Doumergue, p.31.

5. Calvin faculty minutes May 13, 1932: “While realizing that the so-called Calvin seal with the heart and the hand device may seem to some unaesthetic, yet because it was the historical seal of John Calvin and because the motto expresses one of the basic ideas of Calvinism, we therefore join in asking the Board to adopt this as the official seal." (Quotes from Mildred Zylstra, “The Calvin Seal,” manuscript in Meeter Center, p.5)

6. Mildred Zylstra, “the Calvin Seal”

7. see E. Doumergue, p.75f. and Pl.XX.

8. See, for instance, Master of the Spes Nostra, Four canons with ST. Augustine and Jerome by an open grave, in: Netherlandish Art in the Rijksmuseum 1400-1600, ed. Henk van Os; Waanders Publishers, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 2000. p. 80 f.

9. Joel Carpenter, "Agents of the Great Commission,” Keynote Address, Fall Faculty/Staff conference, Sept. 4, 2004.

10. The famous words by John Calvin “Cor meum velut mactatum Domino in sacrificium offero” (without prompte et sincere!) come from a letter he wrote in August of 1541 from Strasbourg to Farell who invited him to return to Geneva as soon as possible. John Calvin was very reluctant to return to that city. But, he wrote …”when I remember that I am not my own, I offer up my heart presented as a sacrifice to God.” (Letters of John Calvin, ed. Jules Bonnet, 1858, vol.1, p. 99. Latin text from Epistolae Nr.248 in Calvini Opera vol.11, 1873.) The historical context gives the Latin words of our motto even more substance and weight. The words Velut mactatum and in sacrificio, (“mactare” means “to slaughter, sacrifice”) point to the radical nature of John Calvin’s obedience – he sacrificed on God’s altar what, at the time, was dearest to him, namely his happy years in Strasbourg and he followed God’s call to Geneva.

11. Unknown artist, broadsheet 1650; “Der Trichter der Weisheit” Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg.

12. Ken Bain, What the Best College Teachers Do, Harvard University Press, 2004.

13. Bain, p. 41.

14. Figur der Grammatik mit Kindern, Southern German, Beginning of 14th centrury, Bayerisches National Museum München, Inv. Nr. 1089.